Manoeuvering

One of the most frequent hull claims are contact damages in conjunction with manoeuvring in ports, entering locks and other confined waters, and currently the trend is rising. In this monthly theme, we highlight the underlying reasons for contact damages, mitigating actions and best practises when it comes to ship handling and Maritime Resource Management (MRM).

Underlying reasons:

Unfavourable meteorological conditions, including strong wind, poor visibility, strong currents (rivers, tidal streams), and ice are the most common cause of contact damages. The second most frequent cause are judgement errors made by the person manoeuvring the vessel and can be related to for example speed, distance(s), and whether the vessel is parallel to berth or lock. Though technical reasons are very seldom recorded as the direct cause of contact damages, however these do occur and can therefore not be ruled out. A common denominator in most contact damage cases is the failure of the MRM elements; communication, coordination, and situational awareness are not maintained throughout a manoeuvre or are lost at some point during manoeuvring.

Mitigating actions:

Make at least two alternative manoeuvring plans to accommodate larger margins, should the meteorological conditions change and/or a technical issue appear and make it too risky or impossible to execute the first plan. Also clearly mark “the point of no return”, up to which the manoeuvre can still be safely exited.

Communicate your plan(s). Every operational role in the manoeuvre is critical and all involved parties need to share a mental picture of what, when and how the operation is to be carried out. A simple but thorough pre-briefing is an effective way to help maintain the participants’ situational awareness throughout the operation.

Be clear on responsibilities and tasks! The Master is always in command of the vessel and may delegate tasks (for example to a pilot), but never the responsibility. The Master should always exercise overriding authority when needed. Encourage “Challenge and Response” from everyone participating in the operation.

Best practices:

Make a “Safe Manoeuvring Plan” for your vessel, where you consider propulsion (main engine(s), thrusters), windage, swept beam, and under keel clearance (UKC). The plan can be made simple so that the opposing and interacting forces are easily plotted to give an idea of where you are on the operational envelope. Alandia can assist in making these plans.

Integrate the MRM concept into all operations and reward desired behaviour, such as “Challenge and Response” and “Closed Loop Communication”.

When a pilot is employed, have short but concise Master/Pilot exchanges where you establish a shared mental picture and agree on the operational plan(s). Be clear and insist that common language is to be used throughout the operation, so that everyone can maintain situational awareness.

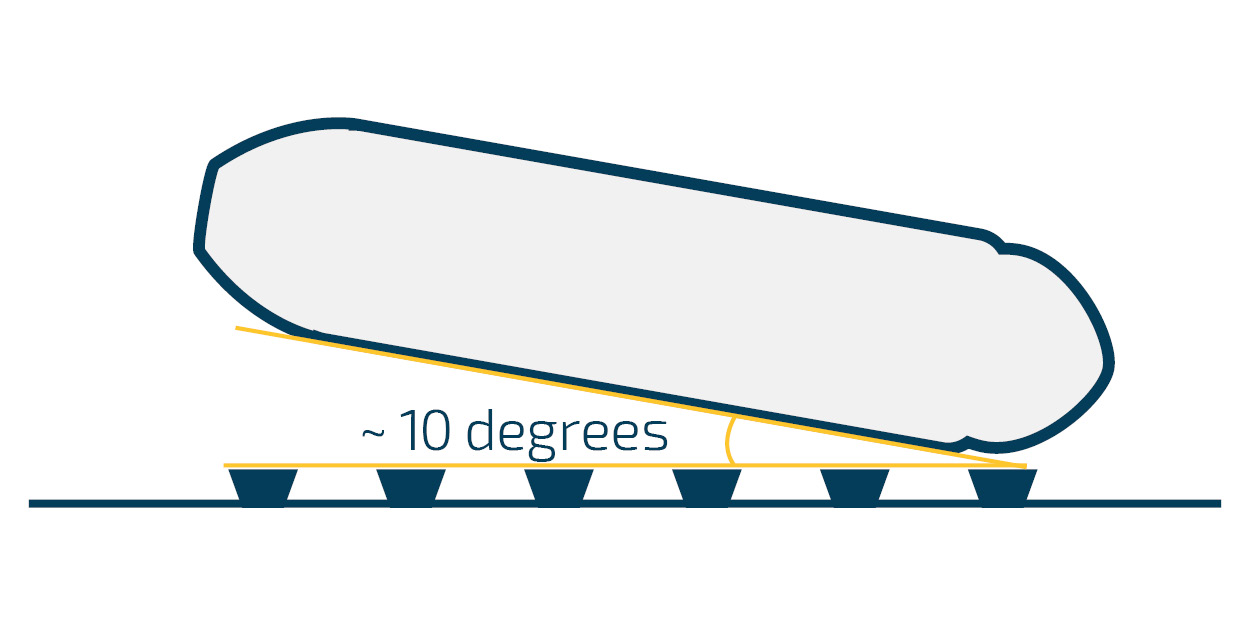

It is best practise to approach locks and berths in a shallow angle. This enables landing the vessel parallel to fenders, dolphins etc. Most fenders are designed around 10-degree compression angles, hence shallow angle of approach and parallel landing!

Insist on common operation language throughout the manoeuvre, including with the pilot and the tugs, if employed. Communicating in several different languages during the same operation increases risks, creates confusion, and effectively removes the MRM elements, such as a shared mental picture and situational awareness.

Train your ship handling skills regularly and mentor all the deck officers to become confident and good ship handlers!

Additional information:

Ship handling centre (solent.ac.uk)

Ship handling training and manoeuvring on manned models – PORT REVEL